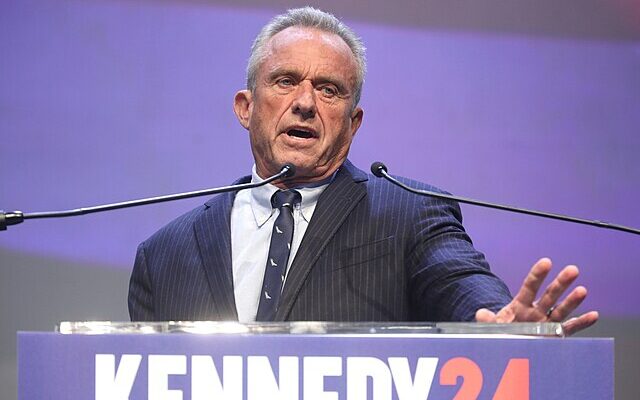

You can’t watch TV without seeing them, and now they’re clearly in the sights of RFK, Jr.’s Make America Healthy Again movement. Television advertisements for prescription drugs—long a staple of primetime broadcasts and morning talk shows—are facing growing scrutiny from key figures in President-elect Donald Trump’s incoming administration. Along with Kennedy, Elon Musk and FCC nominee Brendan Carr have said they plan to take aim at the multibillion-dollar industry.

RFK wants to prohibit drug companies from advertising on TV.

Think about how different the pandemic would have been if legacy media wasn’t in the bag for Pfizer. pic.twitter.com/a1wIuPKIzO

— American Debunk (@AmericanDebunk) November 15, 2024

Since the late 1990s, pharmaceutical companies have poured billions into television advertising, promoting medications with catchy jingles and uplifting visuals of patients reclaiming their lives, writes The New York Times. Analysts estimate that drugmakers often earn five times what they spend on TV ads through increased sales, making advertising a cornerstone of their business strategy. Yet, this well-oiled marketing machine is now encountering resistance at the highest levels of government.

They soon may be coming to an end.

Though it’s not clear how such a ban might happen — Mr. Kennedy has called for an executive order — any attempt would face an uphill battle. Efforts to modestly restrict drug ads have repeatedly been defeated in the courts, often on First Amendment grounds. The first Trump administration tried to require that commercials mention the drug’s price, but a judge blocked the move, saying that it lacked authority from Congress.

The pharmaceutical industry is on track to spend over $5 billion on national television advertisements this year, according to iSpot.TV, a company that tracks ads. The most aggressive campaigns are for newer medications that haven’t yet gone generic but compete in a crowded field of similar drugs to reach patients with common conditions like arthritis and diabetes.

Research has found that the majority of the top-advertised drugs offer little to no medical benefit compared to existing treatments. Many cost tens of thousands of dollars per year.

If Mr. Kennedy wins Senate confirmation to become health secretary and pushes to ban drug ads, he could find allies among doctors. The American Medical Association called for such a ban a decade ago and supported the first Trump administration’s failed push to mention drug prices in ads. He could also find common cause with Americans who love to complain about pharma ads on their screens.

Any attempt to curb pharmaceutical advertising will face steep legal and political hurdles. Courts have consistently ruled that restrictions on drug ads clash with First Amendment protections. A previous Trump administration effort to require ads to disclose drug prices was struck down by a federal judge on the grounds that it lacked congressional authority.

Television networks, heavily dependent on pharmaceutical ad dollars, are also bracing for potential disruption. Prescription drug ads contribute billions annually to networks, with older viewers—a key demographic for both drug marketers and broadcast television—being the primary target audience.

The United States and New Zealand are the only wealthy nations that allow direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising. Critics, including Kennedy, argue that this distinction contributes to overmedication and rising healthcare costs in America. Research shows mixed outcomes from these ads. While they often drive demand for high-cost brand-name drugs, they can also raise awareness about underused treatments, such as vaccines for older adults. However, studies suggest that many heavily advertised drugs offer minimal improvements over existing treatments despite their hefty price tags.

Kennedy has also accused mainstream news outlets of being overly cozy with pharmaceutical companies, alleging that ad revenues influence editorial decisions. He has gone so far as to claim that television networks suppress unfavorable coverage of drugmakers—a charge networks, including CNN, strongly deny. Emily Kuhn, a spokesperson for CNN, clarified to The Times that “advertisers play no role whatsoever in influencing our content or story selection.” Despite these denials, pharmaceutical ads remain omnipresent on major news networks, accounting for nearly half of ad spending on popular nightly news broadcasts.

While television ads are in the spotlight, they represent only a fraction of pharmaceutical marketing budgets. Drug companies spend billions on direct outreach to doctors through free samples, sponsored events, and one-on-one meetings. In 2023 alone, pharmaceutical reps distributed $31 billion in free samples to healthcare professionals, alongside $8 billion spent on direct sales efforts.

If Kennedy secures Senate confirmation and follows through on his push to ban pharmaceutical advertising, he could find support among segments of the medical community. The American Medical Association has supported similar proposals in the past. However, any significant regulatory shift will require overcoming entrenched legal precedents, industry lobbying power, and resistance from media stakeholders.

RFK, Jr. is expected to have one of the more contentious hearings in the Senate among Trump’s cabinet picks.